Messier 42 (M42), the famous Orion Nebula, is an emission-reflection nebula located in the constellation Orion, the Hunter. With an apparent magnitude of 4.0, the Orion Nebula is one of the brightest nebulae in the sky and is visible to the naked eye. It lies at a distance of 1,344 light years from Earth and is the nearest stellar nursery to Earth. The nebula has the designation NGC 1976 in the New General Catalogue.

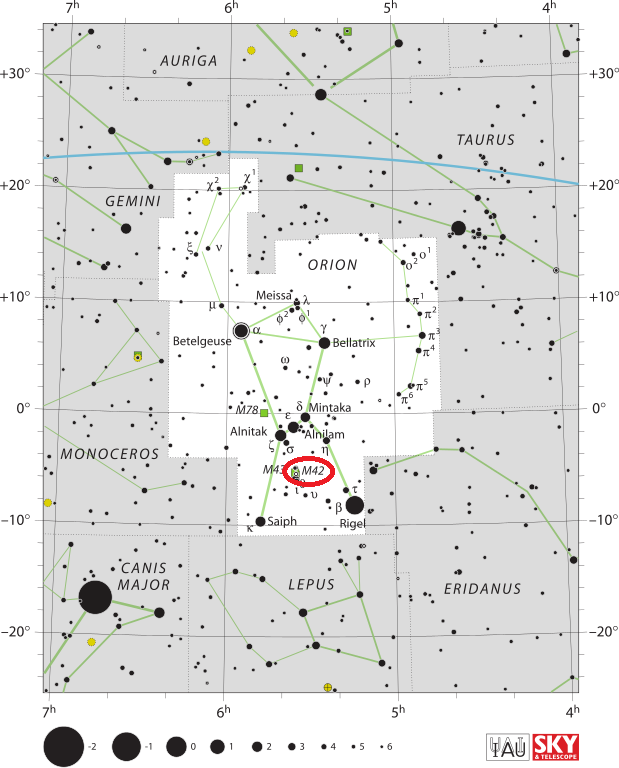

The Orion Nebula is very easy to find as it is located just below Orion’s Belt, a prominent asterism in the winter sky. The nebula appears as the fuzzy middle star in Orion’s Sword, which is formed by a vertical row of three stars (i.e. two stars and M42) south of Orion’s Belt. The nebula can easily be seen in binoculars and small telescopes. Covering more than a degree of apparent sky, the nebula appears over four times the size of the full Moon.

Small telescopes at higher magnifications will reveal the four brightest stars in the Trapezium Cluster, an open cluster of young, hot, massive stars that were formed within the Orion Nebula. The four stars form a trapezoidal shape and energize the surrounding nebulosity.

Orion constellation is easy to identify for its prominent hourglass shape, with the bright supergiants Betelgeuse and Rigel at the upper left shoulder and lower right foot of the celestial Hunter. Orion’s Belt, formed by the bright stars Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka, is in the centre of the hourglass figure. The best time of year to observe M42 is during the winter months, when Orion is high in the sky in the evening.

Messier 42 occupies an area of 65 by 60 arc minutes of apparent sky and its spatial diameter measures 24 light years. The nebula has a mass 2,000 times that of the Sun and contains associations of stars, reflection nebulae, neutral clouds of dust and gas, and ionized gas. It is part of the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex, a larger region of nebulosity that also includes the famous Horsehead Nebula, the Flame Nebula, the emission nebula Barnard’s Loop, De Mairan’s Nebula (M43), and the reflection nebula Messier 78.

The Orion Molecular Cloud Complex covers an area of more than 10 degrees, which is more than half of Orion constellation.

The Orion Nebula is a place of massive star formation and one of the most studied deep sky objects in our vicinity as it allows astronomers to study the process of stars forming from clouds of dust and gas and the photo-ionizing effects of massive young stars that are responsible for the nebula’s glow. New stars are forming throughout the nebula. The temperature in the central region is up to 10,000 K and considerably lower around the edges.

The stars in the Trapezium Cluster emit ultraviolet radiation, heating the surrounding gas and illuminating the nebula. Their stellar winds are also eroding and sculpting the nebula. Most of the ultraviolet ionizing radiation comes from Theta-1 Orionis C, the most massive of the four bright stars in the Trapezium Cluster and one of the most luminous stars known.

Theta-1 Orionis C has the spectral classification O6pe V and the highest surface temperature (40,000 K) of any star visible to the naked eye. It emits 3 to 4 times more photoionizing light than the second brightest star in the cluster, Theta-1 Orionis A.

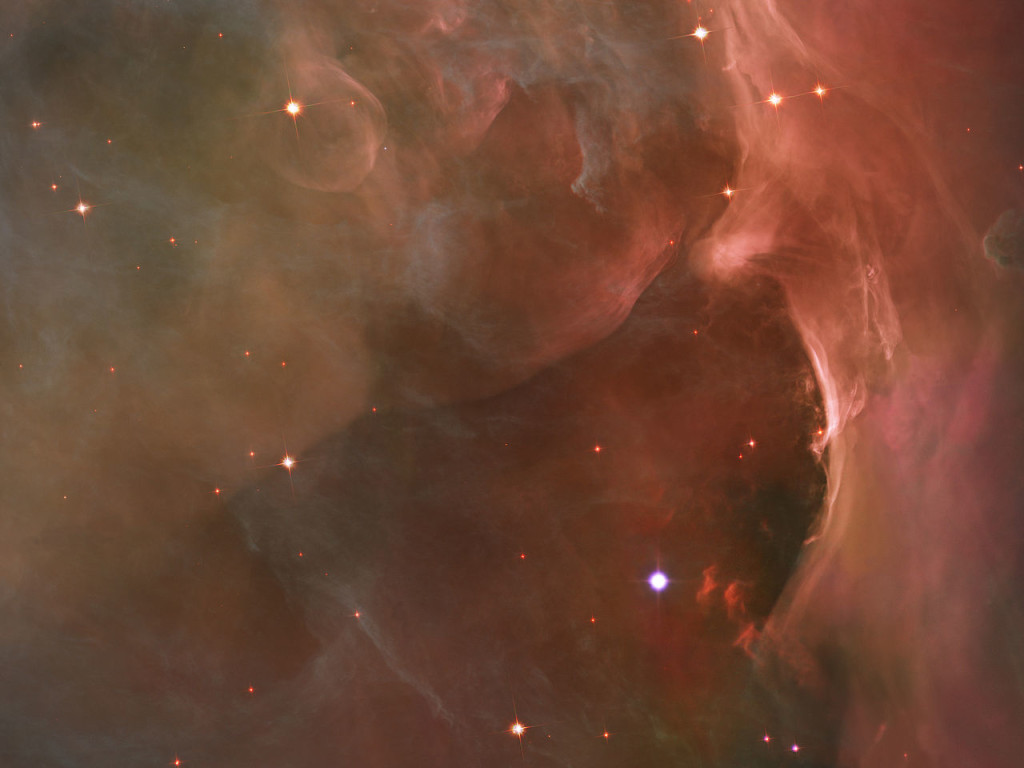

Different parts of the Orion Nebula have been given different names. The bright regions to the sides of the nebula are known as the Wings and the dark lane stretching from the north toward the illuminated region is called the Fish’s Mouth. The wing extension to the south is known as the Sword, the fainter extension to the west is called the Sail, and the bright nebulous region under the Trapezium Cluster has been nicknamed the Thrust.

Messier 42 contains hundreds of very young stars, less than a million years old, and also protostars still embedded in dense gas cocoons. The nebula is home to about 700 stars in different stages of formation. The youngest and brightest members are believed to be less than 300,000 years old, and the brightest of these may be as young as 10,000 years old.

The Hubble Space Telescope has observed more than 150 protoplanetary disks, or proplyds, within M42. These are systems in the first stages of solar system formation.

The brighter discs are indicated by a glowing cusp in the excited material and facing the bright star, but which we see at a random orientation within the nebula, so some appear edge on, and others face on, for instance. Other interesting features enhance the look of these captivating objects, such as emerging jets of matter and shock waves. The dramatic shock waves are formed when the stellar wind from the nearby massive star collides with the gas in the nebula, sculpting boomerang shapes or arrows. Image: NASA, ESA, M. Robberto (Space Telescope Science Institute/ESA), the Hubble Space Telescope Orion Treasury Project Team and L. Ricci (ESO)

In about 100,000 years, most of the nebula will be gone and leave behind a bright, young open cluster of stars surrounded by wispy remains of the former nebulosity, similar to the Pleiades.

FACTS

The Orion Nebula has been known by many cultures since ancient times. It may have been mentioned in the Mayans’ creation myth of the Three Hearthstones. In the myth, the nebula represents the embers of a fiery creation.

The nebula was not mentioned by Ptolemy, Al Sufi or Galileo, even though they documented their observations and listed a number of other objects in their works. Ptolemy catalogued the nebula as a single bright star in 130 AD, as did Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century and German astronomer Johann Bayer in 1603. Bayer catalogued it as Theta Orion in his star atlas Uranometria. Galileo saw several faint stars in the region in 1610, but did not see the surrounding nebula.

The first to identify M42 as a nebula was the French astronomer Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, who observed it with a refractor on November 26, 1610.

Swiss Jesuit astronomer and mathematician Johann Baptist Cysat is credited for the first published observation of the Orion Nebula. The nebula was included in his monograph on the comets, published in 1619. Cysat compared the nebula to a bright comet he had observed in 1618 and described its appearance through his telescope: “one sees how in like manner some stars are compressed into a very narrow space and how round about and between the stars a white light like that of a white cloud is poured out.”

While Cysat may have also provided the first description of the Trapezium Cluster, noting that the central stars were a “rectangle,” the discovery of the cluster is credited to Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei, who detected three of the four main stars on February 4, 1617.

The first published sketch of the Orion Nebula (1659) was made by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens in 1656. Huygens wrote:

There is one phenomenon among the fixed stars worthy of mention, which as far as I know, has hitherto been noticed by no one and indeed, cannot be well observed except with large telescopes. In the sword of Orion are three stars quite close together. In 1656 as I changed viewing the middle one of these with the telescope [a 23-foot FL refractor], twelve showed themselves – not an uncommon circumstance. Three of these almost touched each other and, with four others, shone through a nebula so that the space around them seemed brighter than the rest of the heavens which was entirely clear and appeared quite black, the effect being that of an opening in the sky through which a brighter region was visible.

Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Hodierna, who discovered a number of Messier objects, made the first known drawing of the Orion Nebula and the three stars in the Trapezium Cluster.

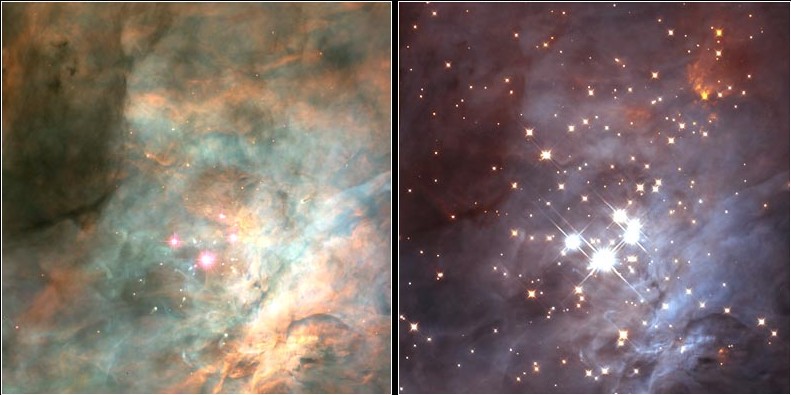

The image on the left, an optical spectrum image taken with Hubble’s WFPC2 camera, shows a few stars shrouded in glowing gas and dust. On the right, an image taken with Hubble’s NICMOS infrared camera penetrates the haze to reveal a swarm of stars as well as brown dwarfs. Source: https://hubblesite.org/newscenter/newsdesk/archive/releases/2000/19

Credits for near-infrared image: NASA; K.L. Luhman (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Mass.); and G. Schneider, E. Young, G. Rieke, A. Cotera, H. Chen, M. Rieke, R. Thompson (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Ariz.)

Credits for visible-light picture: NASA, C.R. O’Dell and S.K. Wong (Rice University)

English astronomer and physicist Edmond Halley included the Orion Nebula in his list of six nebulae in 1716. The other “nebulae” were the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31), the globular clusters Messier 13 (Hercules Globular Cluster), Messier 22 (Sagittarius Cluster) and Omega Centauri, and the open cluster Messier 11 (Wild Duck Cluster).

Charles Messier discovered the nebula and the three stars in the Trapezium Cluster on March 4, 1769, and subsequently included the object in his catalogue as M42. He noted, “Position of the beautiful nebula in the sword of Orion, around the star Theta which it contains with three other smaller stars which one cannot see but with good instruments.“

The Orion Nebula was a well-known object at the time, much like Praesepe and the Pleiades, and not likely to be confused for a comet, but Messier added these to his catalogue nonetheless. This is what he wrote about M42 in the first Messier catalogue:

I have examined a large number of times the nebula in the sword of Orion, which Huygens discovered in the year 1656, & of which he has given a drawing in the work which he has published in 1659, under the title Systema Saturnium [Saturnian System]. It has been observed since by different Astronomers. M. Derham, in a Memoir printed in the Philosophical Transactions, no. 428, page 70, speaks of that nebula which he has examined with a reflecting telescope of 8 feet [FL]. Here is the translation of what he has reported in this Memoir.

“[But] only that in Orion, hath some Stars in it, visible only with the Telescope, but by no Means sufficient to cause the Light of the Nebulose there. But by these Stars it was, that I first perceived the Distance of the Nebulosae to be greater than that of the Fix’d Stars, and put me upon enquiring into the rest of them. Every one of which I could very visibly, and plainly discern, to be at immense Distance beyond the Fix’d Stars near them, whether visible to the naked Eye, or Telescopick only; yea, they seemed to be as far beyond the Fix’d Stars, as any of those Stars are from Earth.”

M. le Gentil also examined this nebula with ordinary refractors of 8, of 15 & of 18 feet [focal] length; as well as a Gregorian telescope of 6 feet, which belongs to Mr. Pingré. He has published his observations in a Memoir which can be found printed in the Volumes of the Academy, year 1759, page 453. There is a joint of the drawings which he had made of it at that time, as well as those of Huygens & of Picard; these drawings differ from each other, so that one may suspect that this nebula is subject to sort of variations. Here is what I have reported about that nebula in the Journal of my Observations. On March 4, 1769, the sky was perfectly serene, Orion was going to pass the meridian, I have directed to the nebula of this constellation a Gregorian telescope of 30 pouces focal length, which magnified 104 times; one saw it perfectly well, & I drawed the extension of the nebula, which I compared consequently to the drawings which M. le Gentil has given of it, I found some differences. This nebula contains eleven stars; there are four near its middle, of different magnitudes & strongly compressed to each other; they are of an extraordinary brilliance: here is the position of the brightest of the four stars, which Flamsteed, in his catalog, designated by the greek letter Theta, of fourth magnitude, 80d 59′ 40″ in right ascension, & 5d 34′ 6″ in southern declination: this position has been deduced from that which Flamsteed has given in his catalog.

Messier catalogued the detached northeastern part of the nebula as a separate object, Messier 43. This portion of the nebula was first reported by French astronomer Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan and is known as De Mairan’s Nebula.

There are several fainter reflection nebulae in the vicinity of M42, to the north, that were later catalogued as NGC 1973, NGC 1975 and NGC 1977. These nebulae partially reflect the light of the Orion Nebula. William Herschel discovered NGC 1977, and the other two were first reported by the German astronomer Heinrich Louis d’Arrest.

The Orion Nebula was the first deep sky object William Herschel observed in his 6-foot reflecting telescope in 1774. He wrote:

The nature of diffused nebulosities is such that we often see it joined to real nebulae; for instance of this kind we have the following fourteen objects [including M42]…

No. 42 of the Connoissance is the great nebula in the constellation Orion discovered by Huygens. This highly interesting object engaged my attention already in the beginning of the year 1774, when viewing it with a Newtonian reflector I made a drawing of it, to which I shall have occasion hereafter to refer; and having from time to time reviewed it with my large instruments, it may easily be supposed that it was the very first object to which, in February 1787, I directed my forty feet telescope. The superior light of this instrument shewed it of such a magnitude and brilliancy that, judging from these circumstances, we can hardly have a doubt of its being the nearest of all the nebulae in the heavens, and as such will afford us many valuable informations. I shall however now only notice that I have placed it in the present order because it connects in one object the brightest and faintest of all nebulosities, and thereby enables us to draw several conclusions from its various appearances.

The first is that the extensive diffused nebulosities contained in the objects of the preceding articles are of the same nature with the nebulosity in this great nebula; for when we pursue it in its extensive course it assumes precisely the same appearance as the before-mentioned diffused nebulosities.

The second consequence we may draw from the circumstance of its containing both the brightest and the faintest nebulosity joined in one object is a confirmation of an opinion already conceived in the second article [on “extensive diffused nebulosities”], namely, that the range of the visibility of nebulous matter is what may be called very limited. The depth of the nebulae may undoubtedly be exceedingly great, but when we consider that its greatest brightness does not equal that of small telescopic stars, as may be seen by comparing four of them situated within the inclosed darkness of the nebula, and several within its brightest appearance, with the intensity of the nebulous light; it cannot be expected that such nebulosities will remain visible when exceedingly farther from us than this prime nebula: the ratio of the known decrease of light will not admit a great range of visibility within the narrow limits whereby this shining substance can affect the eye.

From this argument a secondary conclusion may be drawn, which adds to what has already been said in the foregoing article, namely, that if our best telescopes cannot be expected to reach the nebulous matter, which by analogy we may suppose to be lodged among the very small stars plainly to be seen by them; the actual quantity of its diffusion may still farther exceed even the vast abundance of it already proved to exist. A nebulous matter, diffused in such exuberance throughout the regions of space, must surely draw our attention to the purpose for which it may probably exist; and it must be the business of a critical inquirer to attend to all the appearances under which it will be exposed to his view in the following observations.

German astronomer Johann Elert Bode offered the following observation:

[This] Is the most remarkable nebula in the sky, 6′ large.

The location of the remarkable nebulous region at the sword of Orion is given very indefinite in most of the sky charts and astronomical scripts known to us. But the 15th figure depicts its actual location correctly. The star Theta, which is the one in the middle at the sword, and was described as double by Flamsteed, is situated in the middle of this nebula. 1. Theta appears fourfold in good telescopes, as it has 3 small stars close to it to the east; 2. Theta is close to the east near the previous one and has two small stars east and near it. These indicated seven stars are all involved in a vivid nebula or luminous glow, which appears inclined from evening to morning, in an elongated and curved tongue-shaped figure. Close to the north of this nebula, a small star appears which has something nebulous around it (M43). About 32′ north of 1 and 2 Theta are the stars 1 and 2 c Ori; and about equally south of them is the star Jota after Flamsteed.

Admiral William Henry Smyth observed M42 in January 1834 and wrote:

A multiple star, the beautiful trapezium in the “Fish’s mouth” of the vast nebula in the middle of Orion’s sword-scabbard. A 6 [mag], pale white; B 7, faint lilac; C 7 1/2, garnet; D 8, reddish; and E 15, blue. This was entered 1 H. III. [M43], in November, 1776, and had the honour of being the object to which the grand forty-foot reflector was first directed, in February, 1787, under the designation “quadruple.” As a trapezium it was gazed at, measured, and delineated, for upwards of fifty years, when Struve announced it “quintuplex,” by the addition of the little star E. Now when we consider the eye of WH [William Herschel], the measures of South, and the rigorous examination of JH [John Herschel], this little companion must be looked upon as variable; indeed nothing can exceed the confidence with which H. [John Herschel] assured me, of its not being visible when he made the beautiful drawing of 1824, confirmed by himself and Mr. Ramage on the 3rd of March, 1826: and yet in 1828 it was not to be overlooked but by wilful inattention. Mr. Dawes afterwards saw it well with his five-foot telescope. (…)

Ptolemy, Tycho Brahé, and Hevelius, ranked Theta of the 3rd magnitude, as did Bayer in his Uranometria, all evidently supposing the two contiguous stars and the bright spot constituted a single star. The effulgent nebula in which it is placed, familiarly called the Fish’s head, with its streaming appendages, certainly has an irregular resemblance to the head of some monster of the polyneme genus. Its brilliancy is not equal throughout, but the glare of the brighter parts gives intensity to the darkness which they bound, and excites a sensation of looking through it into the luminous regions of illimitable space, a sensation not entirely owing to any optical illusion of contrast.

John Herschel catalogued the nebula as h 360 and later added it to the General Catalogue as GC 1179.

English amateur astronomer William Huggins used his visual spectroscopy method to reveal that the nebula was made up of “luminous gas” in 1865. Huggins noted:

The light from the brightest parts of the nebula near the trapezium was resolved by the prisms into three bright lines, in all respects similar to those of the gaseous nebulae, and which are described in my former paper.

These three lines, indicative of gaseity, appeared (when the slit of the apparatus was made narrow) very sharply defined and free from nebulosity; the intervals between the lines were quite dark.

When either of the four stars Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta Trapezii was brought upon the slit, a continous spectrum of considerable brightness, and nearly linear (the cylindrical lens of the apparatus having been removed), was seen, together with the bright lines of the nebula, which were of considerable length, corresponding to the length of the slit. The fifth star Gamma’ and the sixth Alpha’ are seen in the telescope, but the spectra of these are too faint for observation.

The Orion Nebula was the first nebula ever to be photographed. American amateur astronomer Henry Draper was the first to photograph the nebula on September 30, 1880. Draper used an 11-inch refractor and the new dry plate photographic process to make a 51-minute exposure of M42.

The details of the nebula were first revealed in a set of images taken by the English amateur astronomer Andrew Ainslie Common in 1883. He also used the dry plate process as well as a 36-inch reflector to record several images in exposures of up to 60 minutes.

Swiss-American astronomer Robert Julius Trumpler was the first to use the name Trapezium Cluster for the young open cluster inside M42 after discovering that the fainter stars near the Trapezium asterism formed a cluster. He estimated the cluster’s distance at 1,800 light years.

The Hubble Space Telescope took the first photos of the Orion Nebula in 1993 and has observed the object many times since.

INFORMATION

| Object: Nebula with open cluster |

| Type: Emission/Reflection |

| Designations: Messier 42, M42, Orion Nebula, Great Orion Nebula, NGC 1976, Sharpless 281, 3C 145, LBN 209.13-19.35, LBN 974, PKS 0532-054, MWSC 0582 |

| Features: Trapezium Cluster |

| Constellation: Orion |

| Right ascension: 05h 35m 17.3s |

| Declination: -05°23’28” |

| Distance: 1,344 light years (412 parsecs) |

| Apparent magnitude: +4.0 |

| Apparent dimensions: 65′ x 60′ |

| Radius: 12 light years |

LOCATION

IMAGES

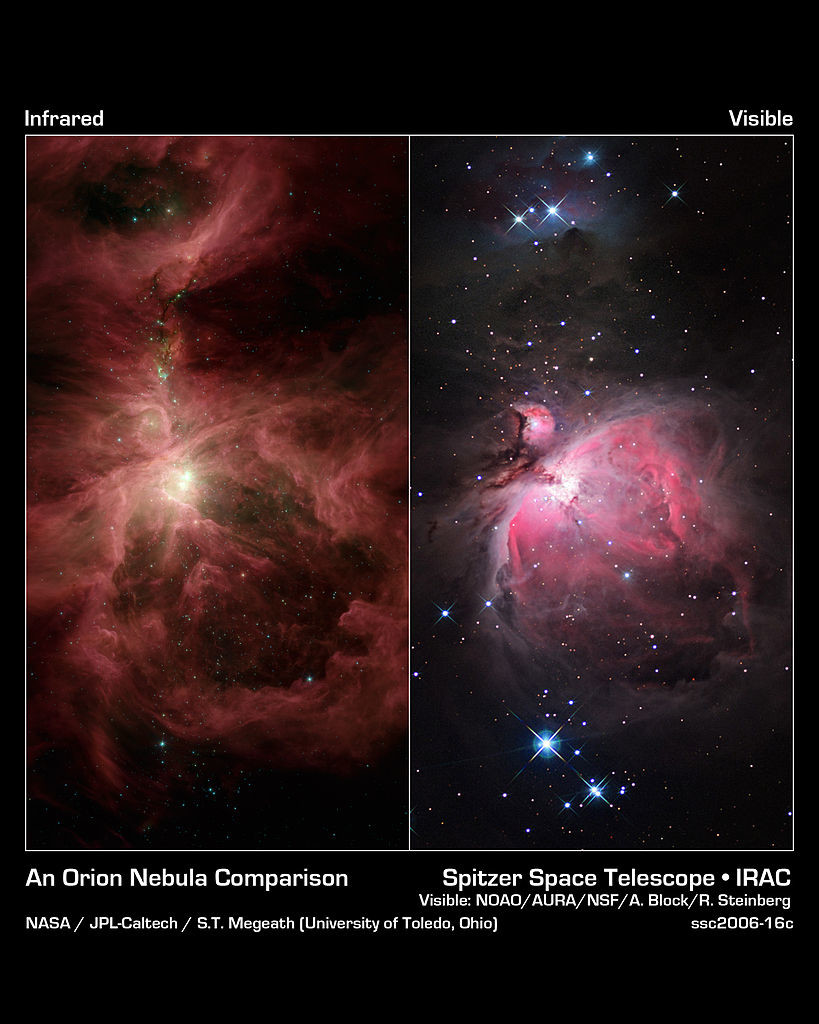

Together, the telescopes expose the stars in Orion as a rainbow of dots sprinkled throughout the image. Orange-yellow dots revealed by Spitzer are actually infant stars deeply embedded in a cocoon of dust and gas. Hubble showed less embedded stars as specks of green, and foreground stars as blue spots. Stellar winds from clusters of newborn stars scattered throughout the cloud etched all of the well-defined ridges and cavities in Orion. The large cavity near the right of the image was most likely carved by winds from the Trapezium’s stars.

This image is a false color composite where light detected at wavelengths of 0.43, 0.50, and 0.53 microns is blue. Light at wavelengths of 0.6, 0.65, and 0.91 microns is green. Light at 3.6 microns is orange, and 8.0 microns is red. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/STScI