Messier 76 (M76), also known as the Little Dumbbell Nebula, is a planetary nebula located in the constellation Perseus. The nebula lies at an approximate distance of 2,500 light years from Earth and has an apparent magnitude of 10.1. It has the designations NGC 650 and NGC 651 in the New General Catalogue as it was once believed to consist of two separate emission nebulae.

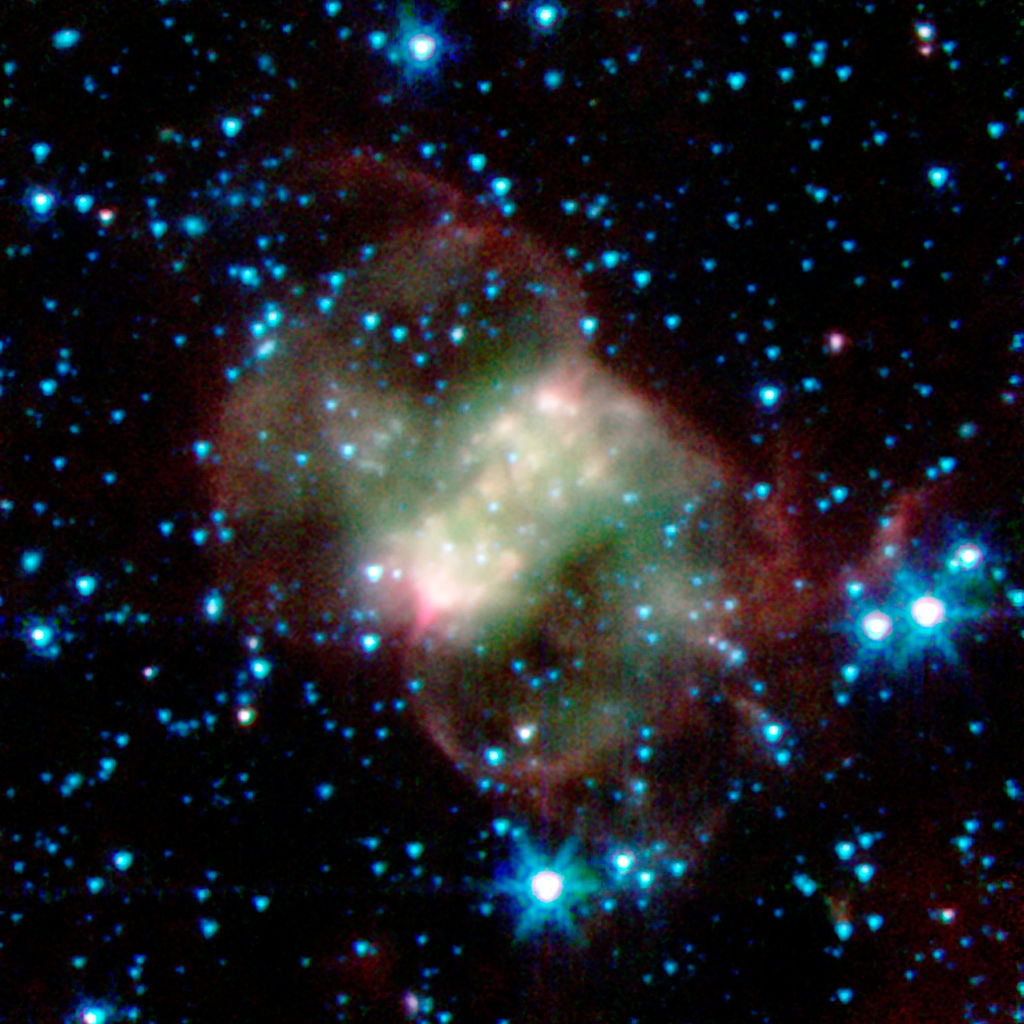

The Little Dumbbell Nebula is sometimes also called the Cork Nebula or the Barbell Nebula. It occupies an area of 2.7 by 1.8 arc minutes of apparent sky, which corresponds to a spatial diameter of only 1.23 light years. The nebula’s size and faintness makes it one of the most difficult Messier objects to observe.

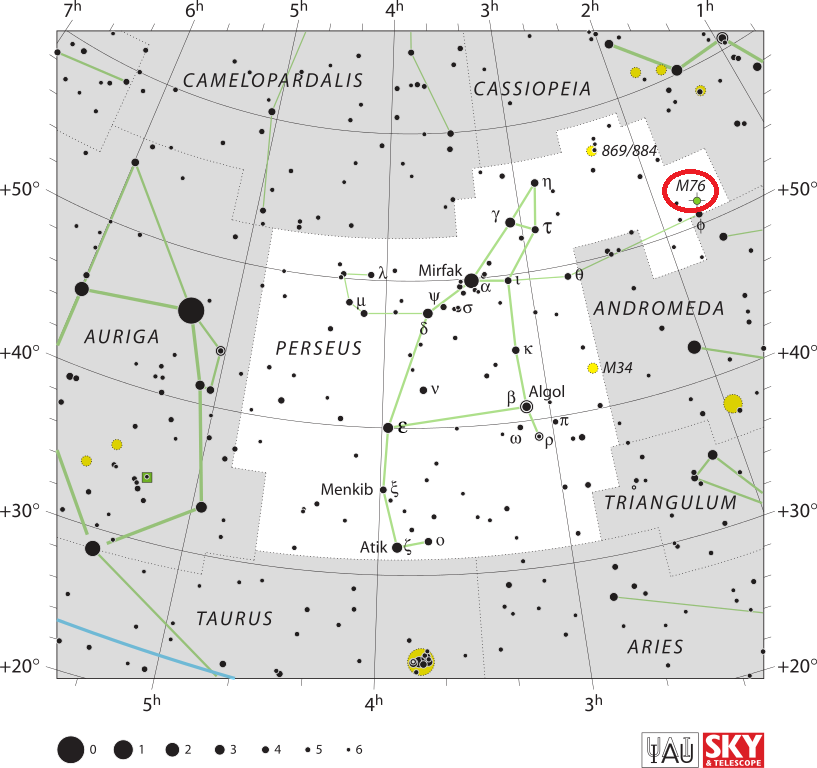

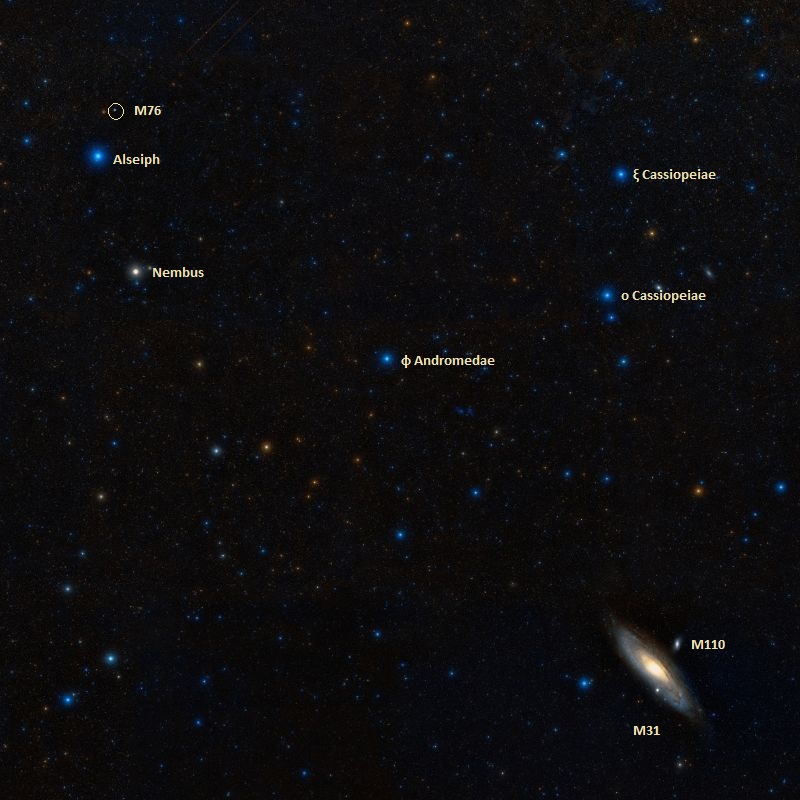

Messier 76 lies in the eastern part of Perseus constellation, next to the border with Andromeda. It is quite easy to find because it is located just south of Cassiopeia’s W asterism and about a degree north-northwest of the magnitude 4.0 star Alseiph, Phi Persei. The nebula is in the same region of the sky as the Andromeda Galaxy (M31).

Large binoculars and small telescopes show M76 as a small, diffuse point of light. The nebula is better seen through medium-sized telescopes. 8-inch telescopes reveal its two lobes and the dark lane separating them, while large instruments show both the double-lobed structure of M76 and the faint halo surrounding it. The best time of year to observe the Little Dumbbell Nebula is during the months of October, November and December. It is a challenging object for southern observers because it never climbs high above the northern horizon when seen from locations south of the equator.

The Little Dumbbell Nebula is one of only four planetary nebulae listed in the Messier catalogue. The other three are the Dumbbell Nebula (M27) in Vulpecula constellation, the Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra, and the Owl Nebula (M97) in Ursa Major.

The Little Dumbbell Nebula was named for its resemblance to the much larger Dumbbell Nebula. Its main body, known as the “cork,“ probably looks like an elliptical, donut-shaped ring when seen face-on, but appears to us edge-on. The gas along the axis of the ring expands more rapidly, forming the nebula’s “wings,” which are fainter than the main body. The cork and the wings are surrounded by an even fainter halo that consists of material that the central star ejected while it was still in its red giant phase.

The Little Dumbbell Nebula was formed when a Sun-like star ran out of fuel in a late stage of its life and then expelled its outer layers. The expelled material was then heated by the radiation of the stellar remnant, producing the glowing clouds that we see as the nebula. The clouds will disperse over the next several thousand years and the central white dwarf will eventually cool and fade away.

Messier 76 is classified as a bipolar planetary nebula (BPNe). The central star, HD 10346, has a visual magnitude of 15.9 and a temperature of about 60,000 K. In fact, M76 is known to have two stars, not one, at the centre. The nebula itself has a surface temperature of about 88,400 K and is moving toward us at 19.1 km/s. Its clouds are expanding at a rate of 42 km/s.

The bright portion of the Little Dumbbell Nebula is about 65 arc seconds in diameter and it is surrounded by a halo about 290 arc seconds in diameter.

The Little Dumbbell Nebula was discovered by the French astronomer Pierre Méchain on September 5, 1780. Méchain reported the discovery to his friend and colleague Charles Messier, who subsequently included the nebula in his catalogue of deep sky objects on October 21. Messier wrote:

Nebula at the right foot of Andromeda, seen by M. Méchain on September 5, 1780, & he reports: “This nebula contains no star; it is small and faint”. On the following October 21, M. Messier looked for it with his achromatic telescope, & it seemed to him that it was composed of nothing but small stars, containing nebulosity, & that the least light employed to illuminate the micrometer wires causes it to disappear: its position was determined from the star Phi Andromedae, of fourth magnitude.” (diam. 2′)

William Herschel suspected that M76 was a double nebula, with the two components in contact, and catalogued the second nebula as H I.193 on November 12, 1787. The nebula was later included in the New General Catalogue as NGC 650 and NGC 651, with the latter denoting the eastern portion of M76. Herschel described the object as “two nebulae close together. Both very bright. Distance 2′. One is south preceding and the other north following. One is 76 of the Connoissance.“ He would later add that “their nebulosities run into each other.“

John Herschel added the nebula to the General Catalogue as GC 385, describing it as “very bright; preceding of double nebula.” Like his father, he catalogued the eastern part (H I.193) separately, as GC 386.

Lord Rosse thought the nebula showed evidence of some spiral structure, but was mistaken.

English amateur astronomer and spectroscopy pioneer William Huggins discovered that the nebula’s spectrum was gaseous in 1866. He wrote, “Both parts of this nebula give a gaseous spectrum. The brightest only of the three lines usually present was certainly seen. The second line is probably also present. I suspect a faint continuous spectrum at the preceding edge of No. 386.“

Admiral William Henry Smyth observed M76 in October 1837 and wrote:

An oval pearly white nebula, nearly half-way between Gamma Andromedae and Delta Cassiopeiae; close to the toe of Andromeda, though figured in the precincts of Perseus. It trends north and south, with two stars preceding by 11s and 50s, and two following nearly on the same parallel, by 19s and 36s; and just np of it is the double star above registered, of which A is 9 [mag], white; and B 14, dusky. When first discovered, Méchain considered it a mass of nebulosity; but Messier thought it was a compressed cluster; and WH [William Herschel] that it was an irresolvable double nebula. It has an intensely rich vicinity, and with its companions, was closely watched in my observatory, as a gauge of light, during the total eclipse of the moon, on the 13th of October, 1837, being remarkably well seen during the darkness, and gradually fading as the moon emerged. In 1842, I consulted Mr. Challis upon the definition of this nebula in the great Northumberland equatorial, and he replied: “I looked at the nebula, as you desired, and thought it had a sprangled appearance. The resolution, however, was very doubtful.”

American astronomer Heber Doust Curtis was the first to recognise M76 as a planetary nebula in 1918, even though Welsh amateur astronomer and astrophotographer Isaac Roberts suggested in 1891 that the object may be similar to the Ring Nebula (M57), only seen edge-on. Roberts also discovered that M76 was a single nebula and not a double one. Curtis noted:

Enlarged 5.8 times from a negative of 4h exposure. Central star of magn 16. Quite irregular, but evidently to be included as one of the larger members of the planetary class. The central and brighter portion of the nebula is an irregular, patchy oblong 87″x42″ in p.a. 40deg; from the ends of which faint, irregular, ring-like wisps extend; total length 157″ in p.a. 128 deg. Brightest patch at southern end of central part. Rel. Exp. 20.

FACTS

| Object: Nebula |

| Type: Planetary |

| Designations: Messier 76, M76, NGC 650, NGC 651, Little Dumbbell Nebula, Cork Nebula, Barbell Nebula, CSI+51-01391, IRAS F01391+5119, GCRV 950, HD 10346, PN G130.9-10.5, PK 130-10 1, KP98 1, WB 0139+5119, WD 0139+513, PN ARO 2, PN VV 6 |

| Constellation: Perseus |

| Right ascension: 01h 42.4m |

| Declination: +51°34’31” |

| Distance: 2,500 light years (780 parsecs) |

| Apparent magnitude: +10.1 |

| Apparent dimensions: 2′.7 x 1′.8 |

| Radius: 0.617 light years |

LOCATION